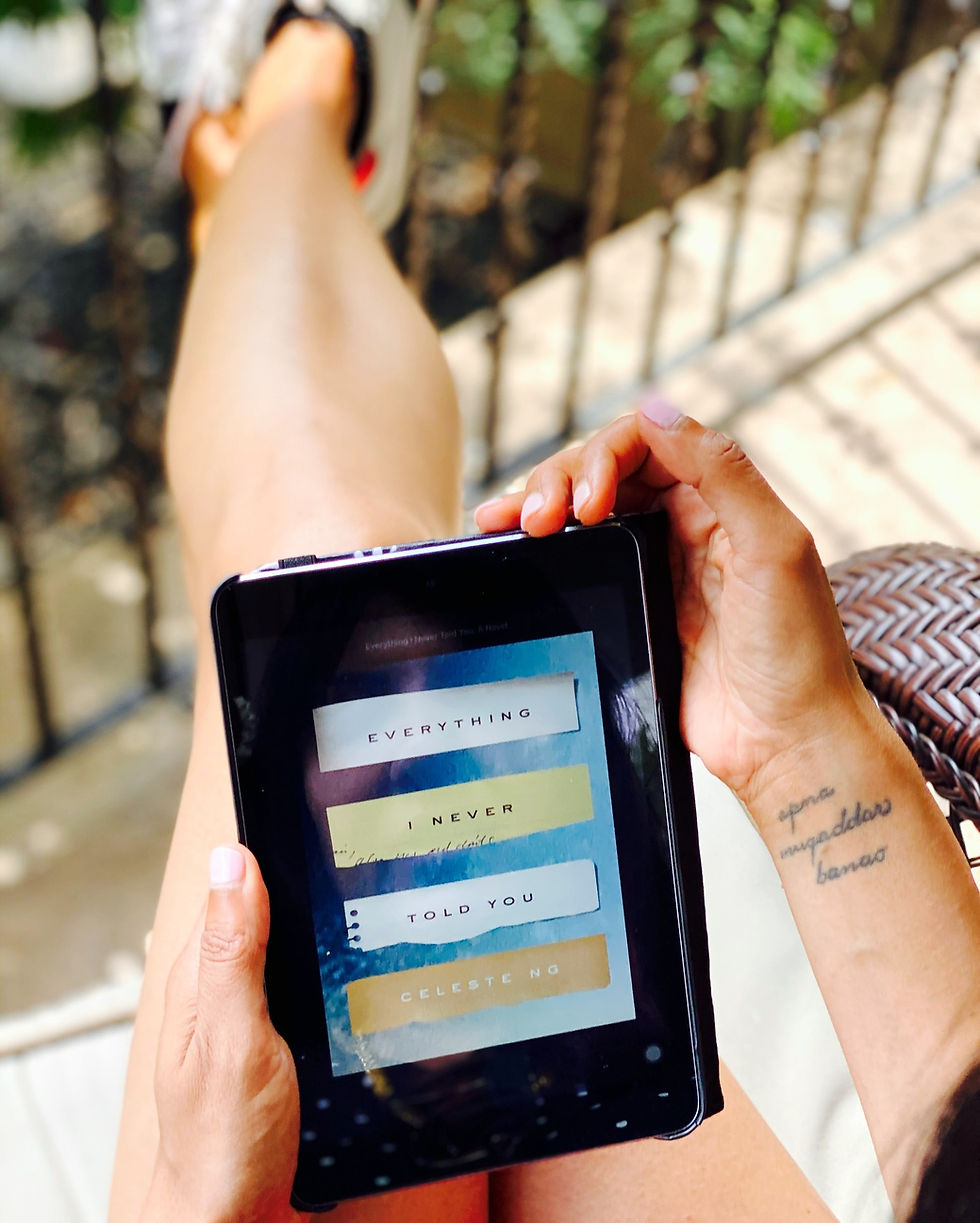

Handling your own problems will kill you. Everything I Never Told You, Celeste Ng’s debut novel, is a perfect example of how handling one's problems alone have both catastrophic and devastating effects. In many ways we are taught to try to be strong, to own our stress, and to overcome it. In short, we are taught that “mental toughness” will get us through. A “strong” person is able to navigate and control their emotions, and allow the stress to drive them to fulfill their goals and succeed in their endeavours. What of the person who can’t? What of the person who is “too sensitive”? What of the person who does not know how to ask for help? So much is happening in the area of mental health development, but what happens when a person, child or adult, can’t handle it yet also cannot seek help? When Lydia Lee on the first page, is found dead at the bottom of a lake at age 15, we the reader, are both confused and devastated. How did this seemingly perfect girl end up dead? Delving into this traumatic, yet cathartic novel, the number one thing to take away is: handling your own stress will kill you.

We first meet wife and mother, Marylin Lee, with former dreams of becoming a doctor, who grew up at a time where a woman's place is in the home. She attempts to fight against this by going to university but cannot handle the stress and backlash of the male-dominated program. As her life progresses, somehow she is caught in the nuances of motherhood, with an existence exactly like that of her homemaker mother. “She thought with sharp and painful pity of her mother [who] ended up alone, trapped like a fly in this small and sad and empty house, this small and sad and empty life. Was she sad? She was angry. Furious at the smallness of her mother’s life” (Ng, 115). Marylin never communicates to her spouse her feelings of unfulfillment. She holds it inside her, raising young children, and it builds and builds. A catastrophic event then only multiplies things, when she quietly snaps. In fact, “quiet” is what the children seem to learn from her.

James Lee, our patriarch, lives a lifetime of feeling less than. The struggles of his immigrant parents teach him to keep his feelings inside, for fear of burdening them. Constant and quiet self-deprecation, born out of living in a ‘white’ city, going to a white school, and then settling in an even more white town, are the pillars upon which James forms his entire identity. He never ever shares this burden with his wife, nor family. He carries it all on his own, which makes the self-loathing of his culture, and the existence of it in his children (particularly in his son), even more pronounced. Never once does he share the stress of this unhappiness with a soul. How can decades of torment be shouldered alone? In turn, James always imagined that his son Nathan would be everything he wasn’t: an all-American boy. As he starts to realize that this is not happening, through his mute lack of processing feelings, and his failure in communication with his son, he ends up inadvertently punishing Nathan. Rather than counsel him on the difficulties of being a visible minority, James hates his son for not being able to overcome them. He is forced to recall a bullying incident from his school days, when a similar incident happens to Nathan. “So part of him wanted to tell Nath that he knew: what it was like to be teased, what it was like to never fit in. The other part wanted to shake his son, to slap him. To shape him into something different” (Ng, 132). How ironic that his own children experience the same racism as him, for Lydia too is suffering, and each one is handling their pain in isolation? “Sometimes you didn’t think about it at all. And then sometimes you noticed the girl across the aisle watching, the pharmacist watching, the checkout boy watching, and you saw yourself reflected in their stares: incongruous...every time you saw yourself from the outside, the way other people saw you, you remember all over again. You saw it in the sign at the Peking Express -- a cartoon man with a coolie hat, slant eyes, buck teeth, and chopsticks. You saw it in the little boys on the playground, stretching their eyes to slits with their fingers -- Chinese -- Japanese look at these -- and in the older boys who muttered ching chong ching chong ching as they passed you on the street…” (Ng, 271). If only the Lees had communicated, talked, cried, and somehow managed their emotions and sentiments together, they could have processed and dealt with it. Together. Handling stress on your own does not make you strong. It only serves to weaken you.

When life gets hard everyone chooses to handle it differently. Some people scream and fight with those closest to them, or take it out on some sort of proverbial punching bag. Others will bottle it up inside, and wait until the stress reaches its peak. The commonality between all characters in this novel is that they are all quiet about it. Marilyn and James, by relying solely on themselves to deal with their stress, ironically end up sucking the life, so to speak, out of every child. None of these children (who are quite young) are counselled, because of Marylin and James wanting to handle ‘grown-up stuff’ on their own. How can parents, the adults in the family, not see that keeping family members in the dark only hurts them more?

I myself, in my early 20s, experienced the tragic loss of an older sibling. The pain of it was so great that we did not, could not talk about it. Looking back, that silence was oh so devastating. Similar to Marilyn and James, my parents independently shouldered this tragedy. Is it better for pain to be handled by one, or is it better that it is shared, and thereby diluted and lessened? And sure enough, my daughter would say that because of my ‘rubber ducky moment’, I am now an over-sharer of information. An over-talker. What got me through my pain, was in fact communication, talking, and sharing of that pain -- with people outside of my family. Not sharing one’s pain or grief, not leaning on those around you, creates irreparable damage. In the case of the Lees, all this does is create an emotional panic in the children -- who are confused, terrified and afraid -- which will live in them for a lifetime. This sadness will even spill over, into the third child Hannah, who isn’t even born when it all happens. All three children live to mimic the lack of communication in the family. All three children live to keep their stress to themselves. Born from parents who never tried to ask for help, is almost their sad and unfortunate birthright.

What is a family? It can be defined in many different ways, specifically in modern society. One commonality in all families is that they consist as a group of individuals that are on the same team, working together towards common goals: love, harmony, and unity. Every family comes under stress, this is an indisputable fact. Members who insist on shouldering the stress independently, are not functioning fully as family/team members. If a teammate comes under fire, the whole team does. There is an old saying, “we are only as strong as our weakest link”. If the weakest link is in pain and under stress and the others do not know, then how strong can that family really be? The Lee family is weak to the core. The lack of communication, lack of honesty, and lack of sharing are all culprits in this reality. James “has spent the past three weeks in his office, although the university has offered to have someone else finish out the term. Her mother has spent hours and hours in Lydia’s room, looking and looking at everything but touching nothing. Nath roams the house like a caged beast, opening cupboards and shutting them, picking up one book after another, then tossing them down again. Hannah doesn’t say a word. Don’t talk about Lydia. Don’t talk about the lake. Don’t say a word” (Ng, 151). What if when stress reared its ugly head, rather than protecting their family members, each person leaned inwards and asked for help? What if that “weakness” was handled with an attempt at gaining strength, by actually siphoning that strength from others and vice versa. What if the Lee family had done this? Would Nath, the criticized and condemned son, who in his father's eyes was a mirror image, actually then build on his father's shortcomings? Would Hannah, the neglected and ignored third child, be taught how to handle her sister’s death, and process her grief? Would Marylin, the matriarch, with unfulfilled career ambitions and feminist ideals put by the wayside, be able to communicate her sadness to her husband and children, and in this way overcome it? So much so, that she wouldn’t have to think: “Please...In this world is all she cannot phrase, even to herself. Please come back, please let me start over, please stay. Please” (Ng, 347). Would James, the head of the family, with a classic immigrant inferiority complex, share this pain with his white wife and biracial children, and thus survive in a white man's world? Then maybe he would not have to say: “If she were a white girl, [the police] would keep looking [for her killer]” (Ng, 283). Maybe he would not have to recall a memory:

“You’re the first Oriental boy to attend Lloyd,” his father reminded him. “Set a good example”. That first morning, James slid into his seat and the girl next to him asked, “What’s wrong with your eyes?” It wasn’t until he heard the horror in the teacher’s voice -- ‘Shirley Byron!’ -- that he realized he was supposed to be embarrassed. The next time it happened, he learned his lesson, and turned red right away” (Ng, 66).

And finally, would silent Lydia, be alive today? For keeping it all inside, will definitely kill you in the end. Read Celeste Ng’s debut novel in order to delve more into this crucial and painful tale.

Sources:

Ng, Celeste. Everything I Never Told You. New York: Penguin Press HC, 2014.

Comments